Nullum Crimen Sine Lege, Nulla Poena Sine Lege

On 21 March 1997, animals were given rights at common law in Scotland. It is a ruling that we have never managed to overturn and the following passage details how the judgement was made including all further judgments since that have upheld the ruling.

R Hill & Co maintains that our cattle were stolen by Sheriff Michael Fletcher and Procurator Fiscal David Howdle. David Howdle orchestrated and Sheriff Fletcher sanctioned, the removal and unbelievably the sale and destruction of R Hill & Co's entire herd prior to any criminal proceedings. In so doing both men disregarded with total disdain an 85 year old statute and the rule of law.

David Howdle libelled a charge of cruelty to animals at common law in a petition that sought warrant permitting the entire herd of cattle from Powhillon farm to be removed and either sold, slaughtered or destroyed. Cruelty to animals is not a common law crime as recorded in Shepherd v. Menzies, 1900 2 F 443. As per Lord Kyllachy's judgement, which was an opinion held by Lord Justice-Clerk, Lord Trayner and Lord Moncreiff: “It has of course to be assumed that cruelty to animals is an offence,—that is to say, a crime. It is not so at common law, but it is made so by the Statute 13 and 14 Vict. cap. 92”. ....'Refer to last paragraph of third sheet (which has page number 445)'

Theft in Scots Law is defined as the wrongful appropriation of the property of another without the true owner’s consent and with the intent to deprive the owner of that property. Michael Fletcher and David Howdle intentionally deprived R Hill & Co of ownership of their cattle via illegal means and ensured that they could never be returned. The actions of Procurator Fiscal David Howdle and Sheriff Fletcher are also monumental in Animal Welfare Law. David Howdle's petition ignored the rights of the true owners of the cattle (R Hill & Co) and the warrant as craved effectively means that animals have rights at common law in Scotland. However the case isn't referenced anywhere and is unreported. The following passage details the events and corruption and criminality.

As stated by Lord Kyllachy, cruelty to animals is not a common law offence and was only made so by Cruelty to Animals (Scotland) Act, 1850 (13 and 14 Vict. cap. 92), sec. 11. When R Hill & Co's cattle were stolen the Cruelty to Animals (Scotland) Act, 1850 had been replaced by the Protection of Animals (Scotland) Act 1912. Section 3 of the 1912 Act clearly states that the court can only deprive a person of ownership if found guilty and if it is proven that an animal would be subject to further cruelty if left in the care of the guilty person. Also considering that the warrant application came before any criminal proceedings the Protection of Animals (Scotland) Act 1912, Section 11 only permits a police constable the rights to remove the animals.

As written by Mike Radford and published by Oxford University Press; Animal Welfare Law in Britain, Regulation and Responsibility, Chapter 14, F:Seizure of Animals: "However, the only circumstances in which statute provides that an animal can be seized solely in the interests of animal protection is where a person having charge of it is arrested by a police constable for an offence of cruelty. In these circumstances the police (but only the police) may take charge of the animal(s) and deposit them in a place of safe custody until the termination of any legal proceedings or the courts order their return. If the matter goes to trial, it takes several months for the case to be resolved, and there is always the possibility of further delay arising from procedural complications or a subsequent appeal. Unless the owner voluntarily relinquishes ownership in the meantime, the animal remains their property, and cannot therefore be rehomed. Furthermore where significant numbers of large animals are involved, such as might be the case where the allegation of cruelty is against a farmer, looking after the animals can present very real logistical difficulties."

No officers of Dumfries and Galloway Constabulary had ever arrested or charged Danny as written by Chief Inspector Kate Thomson. David Howdle clearly knew that cruelty to animals was only a Statutory offence because the day after the cattle were taken, David Howdle as complainer, served the complaint against Danny and it only contained statutory offences. David Howdle dropped common law altogether. David Howdle's motivation for his actions was because he despised Danny Quinn for shooting geese and his hatred was made even more so after he made Danny infamous following his [Howdle] failure in 1993 to prosecute Danny of intentionally shooting "protected" wild geese. David Howdle's hatred continues to this day and on 19 July 2014 two officers (Peter Meechan, shoulder number 80, and Gillian Carson, shoulder number 178) from Police Scotland tried to charge Danny with Breach of the Peace after a complaint was randomly raised by David Howdle that Danny had threatened him and his family. After interviewing Danny the police officers accepted that it was fabricated and walked away. Wasting the time of the police by a false story is itself a common law crime as made so by Kerr v. Hill, 1936 J.C. 71 and yet David Howdle was never charged.

There is a fundamental principle in criminal law in Scotland and Internationally. It is 'nullum crimen sine lege'/'nulla poena sine lege' - there should be no crimes or punishments except in accordance with fixed, predetermined law. Also as written by Sir Gerald H. Gordon, Criminal Law, Second Edition, published by W. Green & Son Ltd: "the declaratory power can be exercised only by the High Court, and probably only by a quorum of that court"". In our terms Procurator Fiscal David Howdle and Sheriff Fletcher could not invent their own law when they stole R Hill & Co's cattle. Quite simply there was no crime at common law and therefore a criminal warrant could not be granted. It was a crime under statute but the 1912 Act clearly stated the cattle could only be removed after the owner was found guilty and if it is proven that an animal would be subject to further cruelty if left in the care of the guilty person. Statute therefore extinguished any other powers at common law that they may have professed to have had to remove the cattle, as premised in cases Watson v. Muir, 1938 J.C. 181 and Normand, Complainer, 1992 S.L.T. 478.

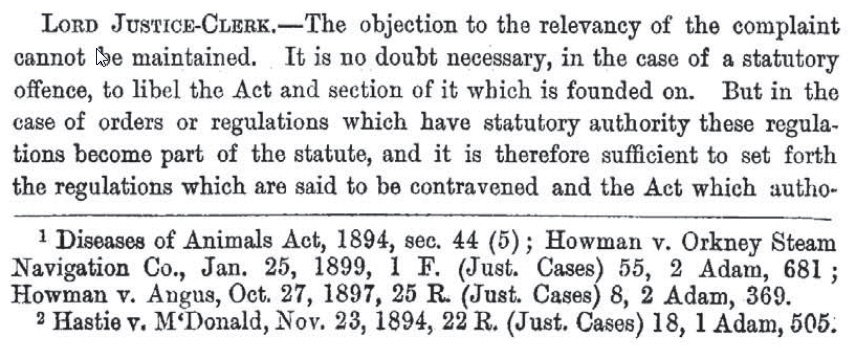

David Howdle petitioned Dumfries Sheriff Court on Tuesday, 18 March 1997 to grant warrant permitting the entire herd of cattle from Powhillon farm to be removed and either sold, destroyed or slaughtered. The application was raised under Section 134 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995, 'Incidental Application' and was sought prior to any proceedings by complaint. No criminal actions had began and R Hill & Co were totally unaware of David Howdle's complaint. The petition contained no Statutory enactment and was therefore libelled at Common Law. With reference to Lord Justice-Clerk's judgement, Jamieson v. Dow 1899 2 F 24:

An incidental application created in summary proceedings is basically just a written application for a warrant. The Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 (c. 46) states the following;

|

(1) This section applies to any application to a court for any warrant or order of court; |

|

|

|

|

(2) An application to which this section applies may be made by petition at the instance of the prosecutor in the form prescribed by Act of Adjournal. |

There are however strict rules to warrants and the authority on the principles for common law warrants is Hay v. H.M. Advocate, 1968 S.L.T. 334. In the opinion of the court the Lords on page 336 state "On the one hand, there is the need from the point of view of public interest for promptitude and facility in the identification of accused persons and the discovery on their persons or on their premises of indicia either of guilt or innocence. On the other hand, the liberty of the subject must be protected against any undue or unnecessary invasion of it. In an endeavour as fairly as possible to hold the balance between these two considerations three general principles have been recognised and established by the Court. In the first place, once an accused has been apprehended, and therefore deprived of his liberty, the police have the right to search and examine him. In the second place, before the police have reached a stage in their investigations when they feel warranted in apprehending him they have in general no right by the common law of Scotland to search or examine him or his premises without his consent. There may be circumstances, such as urgency or risk of evidence being lost, which would justify an immediate search or examination, but in the general case they cannot take this step at their own hand. But in the third place, even before the apprehension of the accused they may be entitled to carry out a search of his premises or an examination of his person without his consent if they apply to a magistrate for a warrant for this purpose. Although the accused is not present nor legally represented at the hearing where the magistrate grants the warrant to examine or to search , the interposition of an independent judicial officer holds the basis for a fair reconciliation of the interests of the public in the suppression of crime and of the individual who is entitled not to have the liberty of his person or his premises unduly jeopardised. A warrant of this limited kind will only, however, be granted in special circumstances. The hearing before the magistrate is by no means a formality, and he must be satisfied that the circumstances justify the taking of this unusual course, and that the warrant asked for is not too wide or oppressive. For he is the safeguard against the grant of too general a warrant."

Procurator Fiscal David Howdle's petition was neither for search or examination of an accused person. In fact Ministers and Local Authorities already had the power to authorize search and examination in accordance with the Agriculture (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1968, without the need for any warrant. The fiscal's petition, was acting in the interests of the cattle only where he made an uncorroborated and unsubstantiated allegation that their removal would protect their welfare (during the removal of the cattle a heifer in calf was destroyed after collapsing with exhaustion, suckling baby calves were stripped from their mothers, 8 of the mothers were destroyed, 15 animals remain unaccounted for). In other words his petition was not to bring about the apprehension of Danny or to gather evidence against him. Howdle was acting on behalf of the cattle and trying to secure a deleterious act of liberty for animals at common law, totally disregarding that the cattle were the property of R Hill & Co. At common law cattle are property and referencing Hume i. 99:- “with respect to domestic creatures, or creatures domitae naturae, such as horses, sheep, poultry and the like, it is equally clear that these are the proper subjects of theft”.

Sheriff Fletcher did not initially grant the warrant at the first hearing on 18 March 1997 and called for a further hearing on Thursday, 20 March 1997. The Sheriff ordered that a copy of the petition be intimated to Danny and requested that he be instructed to attend the court on the aforementioned date. At 17:30, on Wednesday, 19 March 1997 a sergeant from Dumfries and Galloway Constabulary visited the farm and told Danny that he had to attend Dumfries Sheriff Court at 09:30 the following day. No petition was presented to Danny and the only information the sergeant could give him was that Sheriff Fletcher had ordered his attendance.

Danny appeared before Sheriff Fletcher on 20 March 1997. Also in attendance was Deputy Procurator Fiscal Bob Morrison. The petition was read out in court by the Deputy Fiscal and Danny can recall that Sheriff Fletcher asked him whether he agreed that the cattle could be removed. With hindsight Sheriff Fletcher was trying to get Danny to consent to the removal of the cattle. Danny refused to agree to their removal (as recorded in a letter written by Procurator Fiscal David Howlde to Rt. Hon. Russell Brown MP where Howdle wrote "He did oppose it but was unsuccessful") and unleashed sharp words with Sheriff Fletcher and expressed his disbelief that (1) they were going to remove the entire herd of cattle for the reasons given, and (2) they regarded him as being solely responsible considering the facts that the cattle were owned by R Hill & Co and that farming a tenanted holding is an ongoing working relationship between tenant and landlord. Danny denied that he had ever claimed to be solely responsible for farming Powhillon and for the welfare of the animals. Danny also reminded Sheriff Fletcher of his judgement on 3 October 1996 and its relevance and how it implicated Sheriff Fletcher in the present action. After listening to both parties the Sheriff dismissed Danny and returned to chambers.

As stated by Sheriff Principle M M Stephens QC in McMillan v. Procurator Fiscal, Dumfries [2017] SAC (Crim) 2 SAC/2016-000693/AP:- "The prosecutor's motion is placed before "a judge of the court" not before the court of summary jurisdiction itself. When the sheriff considers whether to refuse or grant the prosecutor's motion for a warrant he is essentially exercising his administrative powers and is not sitting as a court of summary jurisdiction." This judgement was based upon Lady Dorrian's opinion in McWilliam v. Harvie 2016 HCJAC 29 in which she referenced an opinion of Lord Gill in Brown v. Donaldson 2008 JC 83 and stated "In granting such a warrant the sheriff is not sitting as a court." Sheriff Fletcher therefore at his own fruition (and not as a court as required by section 3 of the 1912 Act) granted a criminal warrant for a charge at common law upon which there was no crime in Scotland and deprived R Hill & Co of ownership of their property. An act of theft!

On Friday, 21 March 1997 members of the Scottish Office Ministry Veterinary Service turned up with several Quad bikes and 12 animal haulage lorries and proceeded to remove all cattle from Powhillon Farm. Dumfries & Galloway Constabulary were also in attendance where police officers held back R Hill & Co members claiming that the authorities had a signed warrant to remove and sell all of the cattle. A warrant was never served on R Hill & Co (the true owners of the cattle) or indeed Danny.

Eventually in March 2002 we got a copy of the warrant. If you read this story in conjunction with both the disposal of the case and the charges against Danny, you will start to understand how malicious and calculated the Procurator Fiscal’s and Sheriff Fletcher's conduct was from start to finish.

R Hill & Co have pursued this matter for years and what we have written above is based upon what we have learned in the last twenty plus years. Along the way we have had doors slammed in our faces and been bounced from Crown Office to Dumfries Sheriff Court to Dumfries and Galloway Constabulary to Local Procurator Fiscal’s office. Basically no-one is willing to prosecute the prosecutor in Scotland.

We got close once on 2 November 2002, when Inspector Alan McCulloch accepted a written statement and documented evidence from R Hill & Co alleging that Procurator Fiscal, David Howdle had wrongfully and illegally removed R Hill & Co’s cattle from Powhillon farm. By 18 November 2002, David Howdle reported himself to Deputy Crown Agent, Bill Gilchrist and the police investigation was stopped. The police claimed they couldn’t investigate any further because the Deputy Crown Agent was reviewing the allegation. Bill Gilchrist was asked to hand the matter back to the police but refused to do so. On 21 March 2003, R Hill & Co received a response from him which stated that in his 'professional opinion there was absolutely no substance to the allegation that any member of the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service committed a crime in connection with the events relating to the cattle'. Almost a year earlier R Hill & Co had tried to get the Crown Office to investigate the matter but they refused stating that criminal conduct was a matter for the police to investigate.

We also tried petitioning Nobile Officium but the judge at sift was Lord Turnbull who was Advocate Depute at the time Procurator Fiscal David Howdle and the Crown Office stole the cattle. Lord Turnbull ruled in judgement HCA/2017/000009/XM that animals have rights at common law and refused to grant leave for the petition.

Our legal representative Gary McAteer, Beltrami & Co disregarded our claims that this was a wrongful action that had prejudiced the entire criminal case, and claimed nothing could be done until after the trial. This was incorrect because there is a recognised exception in respect of incidental warrants where Lord Cameron in Morton v. Mcleod 1982 S.L.T. 187 referenced Renton and Brown, Trotter, and Moncrieff, that such warrants may be suspended immediately. After the trial Gary McAteer only lodged an appeal against the sentence imposed and not for the first time ignored Danny's instruction.

In Quinn v. Cunningham 1956 J.C. 22 the Lord Justice-General (Clyde) states "It is quite true that the objection to relevancy was not taken at the proper time, and in the ordinary case this would be a conclusive bar to its subsequent consideration. But this well-recognised rule is subject to the exception that the High Court will consider an objection to the relevancy not taken at the proper time if it appears that the complaint cannot be read so as to libel a crime and is therefore fundamentally null-Trotter on Summary Criminal Jurisdiction, p. 324. It would be contrary to justice if this were not so, for, as Lord Mackenzie said in O'Malley v. Strathern, at p. 81, "This Court will not allow a conviction to stand for what is no crime under the law of Scotland." The question of relevancy in the present case raises an issue of fundamental nullity, and must therefore be dealt with by us.". However for years legal professionals have refused to bring a Bill of Suspension on the basis that we have not brought the appeal in the time period permitted and term it that we have acquiesced. And yet in the case of Cantone LTD v John G. McGlennan (Procurator Fiscal, Kilmarnock) 2000 S.C.C.R. 347 Lord Sutherland states "No point was taken at any stage of the proceedings about the alleged incompetence of the interlocutor of 5 December but the advocate depute accepted, before this court, that if there was in fact a breach of the statutory procedure this would result in a fundamental nullity and there would be no question of acquiescence on the part of the appellants.". We have also always faced claims that the warrant is ex facie valid and as such we cannot challenge the actings of Sheriff Fletcher in granting it. This is also untrue as stated by Lady Dorrian in AS v. HM Advocate [2016] HCJAC 126, "Where the challenge to the warrant is one which directly relates to the actings of the judicial office holder in granting it – for example that it was incompetent to grant such a warrant, or that the information upon which it is agreed he proceeded could not suffice to meet the test for granting the relevant warrant, the appropriate course to adopt is a Bill of Suspension."

On the 6th August 2019 we lodged a Bill of Suspension against the warrant. Almost four weeks later Lord Turnbull yet again made the judgement. Astonishingly Lord Turnbull during the four week interim period investigated all prior cases related to the conviction and profoundly ruled in judgement HCA/2019/000009/XJ, that the legality of the warrant was "a matter which has already been ruled upon" by more than one quorum of judges. Animals have rights at Common Law in Scotland. This is now irreversible and means animals have the same rights as you and I and are no longer property. So an animal has for instance a right to freedom and life in Scotland, and has done since 1997. And yet these rights remain an unreported precedent by the courts and legal professionals. It is a monumental anterior ruling to animal rights and liberty.

The simple truth is that the Crown Office and Scotland's Justice System is corrupt and because prosecution in Scotland is solely carried out by the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS), unless they want to prosecute one of their own, we are left to live with the knowledge that Michael Fletcher and David Howdle are deceitful, liars, and thieves and that we will never get justice.

I got sent here via a link, wish I had read it 2 years as I am currently in a massive battle with police Scotland, the p.s.d. and c.o.p.f.s

We were literally frauded by rank members of loreburn st and since then we have had our eyes opened as to the level of corruption in bucleuch st court and beyond.

We personally have had commander s stiff removed (whether temporarily or permanently we won't know until the 2 year investigation concludes) Every member of the rotary club, along with stiff have colluded (our words) to destroy business in Dumfries and you just need to see small business opened and shut in 8 weeks to bring in Julian cowie (ex c.f.o. council). Look at bigger business like comlogon castle, you'll find YOUR aforementioned accused and others along the way.

Hopefully we'll meet along the road